Grandma Kathy Home

So the Cleveland Indians hold a 3-2 edge over the Chicago Cubs as the World Series moves back to Cleveland for at least another game. One particularly sweet spot here is my sentiment that if the Tribe loses, I can be glad for the Cubbies. Both teams are long overdue for a championship.

Alas, the Fall Classic holds diminished interest for me this year. I’m in a space that is best described by a phrase my childhood friend Vince used a lot: tons of bummage.

Joy isn’t in short supply these days; in fact, I have a surplus, more than anybody deserves. The problem is my reaction to our present American season of bummage.

“Do not lose your inner peace for anything whatsoever,” Saint Francis de Sales said, “even if your whole world seems upset.”

Sorry, Francis, but my peace comes and goes. It goes when I assume my fears about the future are predestined. It comes when I forget myself long enough to be touched by grace.

—

“I want to go home,” grandson Cole said.

“But, Cole,” my daughter Elena answered, “you are home.”

“No, I want to go to Grandma Kathy home.”

—

Grandma Kathy and Pop have bored our friends slack-jawed with Cole’s words, but it’s hard to keep quiet. Sometimes a moment kisses your soul and brings hope within reach again.

Cole thinks of Grandma Kathy’s house as home. Do I care that he doesn’t include Pop on the deed? Actually, I like his name better. Kathy drops everything for Cole. They play in her garden and go to the basement and make repairs at her workbench. If she cooks dinner, he stands on a chair at the sink and does a few dishes with a whole bottle of soap.

He calls our den “my room,” and he and Grandma Kathy bunk there when he stays the night, as he did last Saturday. On church mornings, she sits beside him in the backseat for the hour drive to Oniontown.

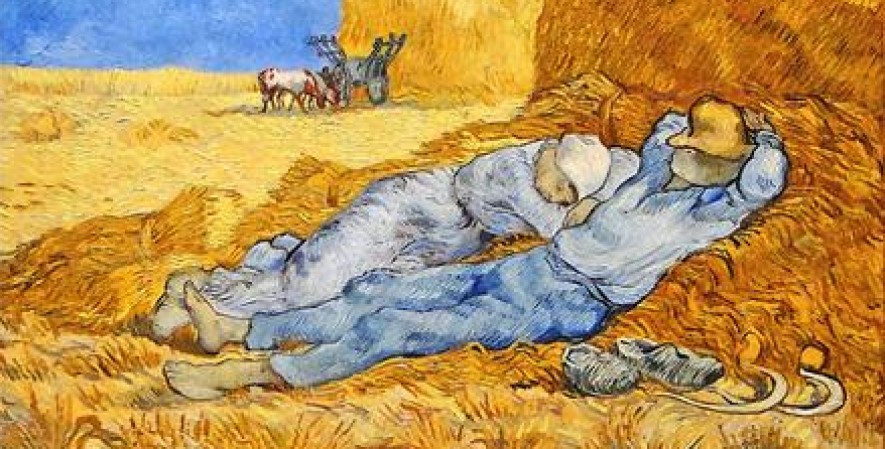

Yesterday my sluggish sermon knocked the kid out, so he crawled under the pew and nodded off at her feet. After worship she let him sleep on, and friends stopped by to chat.

Got insomnia? Come listen to one of my sermons. Bring a pillow, join Cole. (Credit: Kathleen Coleman)

Cole was safe. Grandma Kathy was there.

He didn’t say, “Grandma Kathy’s home.” He said, “Grandma Kathy home.” My wife is home to him. The dwelling and garden are incidental.

Kathy helps Cole sew. He leans against her, watches a movie and eats pretzels and dip. She hustles him off to use the potty like a big boy.

Watching them together, I’m positive of at least one thing that’s right with the world.

—

Fifteen years ago I copied a Bible verse on strips of paper and during a sermon suggested that parishioners put them on their refrigerators.

The light shines in the darkness, and the darkness did not overcome it. (John 1:5)

The light is love. I bet my life that it will win in the end. That doesn’t mean, of course, that my Indians will whip the Cubs. And it especially doesn’t mean that my candidate will prevail.

I don’t for a moment believe that God gives us clean sheets when we’ve messed the bed.

What I do believe is this: love is the only way out of human bummage.

In 1968, during another ugly season, Thomas Merton asked, “Is the Christian message of love a pitiful delusion? Or must one ‘love’ in an impossible situation?”

When I watch a woman and a boy not yet three together, peace fills my lungs. The only way I know to abide in impossible situations is to love.

It seems like hour-by-hour I get hopeless and angry, then hear Saint Francis speaking and try to find my way back to love again. All signs are that I’m delusional.

I want to go to Grandma Kathy home, too, Cole. Let’s live there together.