My stride has been ragged lately, my groove flummoxed. As the poet said, “Nothing is plumb, level, or square.” Or the politician: “What a terrible thing it is to lose one’s mind. Or not to have a mind at all. How true that is.”

Joy is largely to blame. Wife Kathy and I had friends over the other night to catch up. When eyes turned toward me, I said, “I’m happy,” which took some explaining. During the last couple of years, though surrounded by more love and support than anyone deserves, I have been tired and stressed. Maybe burnout is the word. Against all worldly good sense, Kathy and I raided my retirement funds and bought a hermit-sized home. (“You might come to regret that,” an old colleague said, and I couldn’t disagree.) I left a fourteen-year, full-time pastorate and accepted a part-time call seventy miles south of Erie, right through the region’s snow belt. Oh, and we haven’t sold our big house yet.

We Colemans have either lost our minds or found them. It could be that you have to lose one mind to find another. Since gladness and good sense seldom form right angles, I’m not surprised that my stride and groove—constructs of a neurotic brain—are stepping lightly these days.

I didn’t use these words exactly to unpack “I’m happy” for my friends, but they understood. Forced to choose between weary, anxious circumstances standing in crisp formation or calm ambiguity weaving like a drunkard, I’ll take the latter.

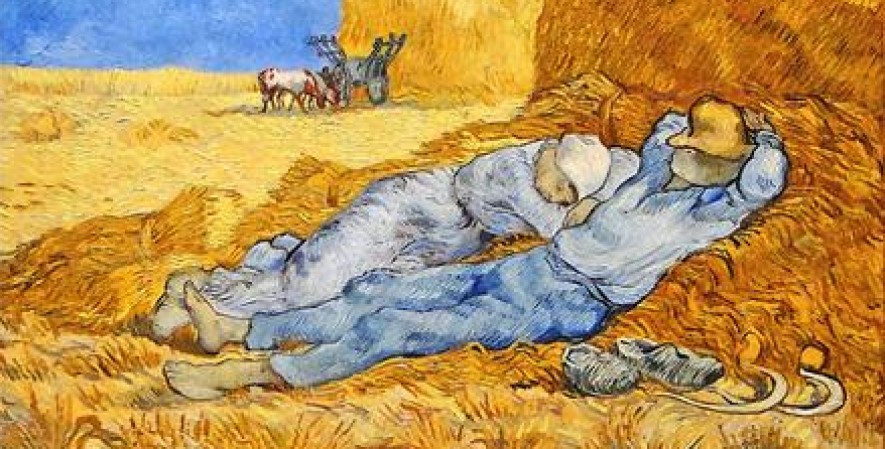

That is to say, I have taken the latter and am learning to embrace uncertainty and surprises. Lately sleep has been whimsical. A new work schedule has taken issue with my long-standing afternoon habit of napping. Like an AARP veteran, I’m reading in bed at 8:30 p.m. and surrendering by 9:00 or 9:30. The result: I wake up at 2:00 a.m., float to the bathroom, return to bed, and abide in a space that is to sleep what free association is to therapy.

Neither refreshed enough to get up nor drowsy enough to disappear, I breathe. Deep breaths, yes, but not those of my past, taken to lift a burden just enough to endure another hour or hush a remark that can’t be retrieved. If insomnia is an enemy, my peculiar wakefulness is a bearer of gifts.

Darkness is upsetting if you’re trying to find something, but it’s a gentle companion if you’re waiting to be found. A few nights ago snoring found me, not my own, but wife’s and dog’s. The sounds, joining for a moment then going their own ways, were blessings. Kathy has been swollen, weak, and achy for the last couple of months, and neither we nor the doctors know why. No matter what noise it makes, her sleep is medicinal. I welcome it. And Watson has weeks rather than months to live. The fatty tumor on his flank is getting hard. The growth on his forehead pains him more by the day. I now hope to come home and find that he has slipped away while dreaming that he and I are going for a run like we did years ago. His snore means that we don’t have to say goodbye quite yet. God bless his kind soul, even our walls and floors will miss him. I think now of his eyes, alive and expectant when Kathy and I left him this morning, and am close to undone.

The first decoration I nailed up in the Coleman’s new home is wisdom from a rabbi, Abraham Joshua Heschel.

Thus spake the rabbi

“Just to be” in a warm bed next to Kathy; “just to live” one more day with Watson: these are the teachings of wakefulness. My chest rises and falls, each in-breath a blessing, each out-breath sacred.

But my darkness isn’t deceptive. It would never say to a lost soul, “Just to be is a blessing.”

Instead I hear, “One corner of your joy will always be uneven, cracked with grief. Whatever mind you possess, it will never be satisfied.”

In this moment, I close my eyes to learn, invite the 2:00 a.m. wakefulness, and hear the rabbi more clearly. Breathing is grace. I survive on love. And I pray: “When my dog dies, Holy One, please help him not to be afraid.”