Field near Prospect, Pennsylvania: a dream view

Solitude, unmasked stars and planets, the shocking cold before dawn, generous draughts of silence: decades ago I wanted this world. Someday, for sure, I would own a house in the sticks with some acres. But—one season following another—age can plow old dreams under, let longing lay fallow, and call a soul to entertain wishes again at the right time or to give them up all together.

The catch is, living more than a holler away from the nearest neighbor is perfect for me. I should want to wind up in the country. I’ve had plenty of great neighbors, some of them like family, but population-density can be a nuisance, right? One former neighbor always fired up her leaf blower whenever I lay down for a nap. It sounded like Carol Channing trying to clear her sinuses. Another neighbor enhanced home security with a nuclear front-yard lamp—impossibly bright. In a step of first-string, All American effrontery, he installed a black shield on the panel facing his house. Why sear every retina on the boulevard, after all? One guy tried to save us by covering the light with a sombrero, only to find it returned to his stoop the next morning.

But such annoyances never drove me from Erie, Pennsylvania, with its 99,542 residents. Columbus and Baltimore, two real cities I’ve called home, were fantastic. So why the persistent sense that I should hear a creek running outside my window? I’ve been thinking in recent years that my dream of rural living was not, in fact, stirred by desire, but by obligation. As a writer who prays a lot, I should want to live a couple hours to the east in Potter County, where deer outnumber humans. Why wouldn’t I want the Coleman home to breathe like the hermitages of my many spiritual retreats in the woods?

This question has occupied me ever since I accepted a call to serve a rural congregation a couple of months ago. The hour’s drive from Erie, where I continue to live, to St. John’s Lutheran Church outside Greenville, Pennsylvania, provides time to sort things out. I listen to tenor arias or fingerstyle guitar or nothing, watch the gray land roll toward the horizon, and let my mind do anything but worry—its default mode.

Wouldn’t the horses I pass on Route 19 be a better routine for my eyes than the strip mall before me at the moment? Shouldn’t I want to move close to the Amish, whose black buggies on District Road tell me to slow down?

I don’t know where “Don’t should on yourself” came from, but the earthy advice points my way. Maybe my closest neighbors should be black bears, but my fifty-four-year-old joys and aches rest easy in a neighborhood, within a stone’s throw of a lady who uses electricity to herd leaves and a better-safe-than-sorry man whose light insults the stars. Being a few minutes away from a ripe avocado, a bottle of cheap red wine, and coffee in a clean, well-lighted place fits me.

Truth: As the days flow by, my old dream yields to a small house in Erie, where I regularly smack my head on the basement ductwork. Less than half the size of the house Kathy and I raised Elena and Micah in, this blue-collar hermitage a mile from my high school feels just right. I don’t want to be anywhere else.

Out the Pastor’s Study window at St. John’s

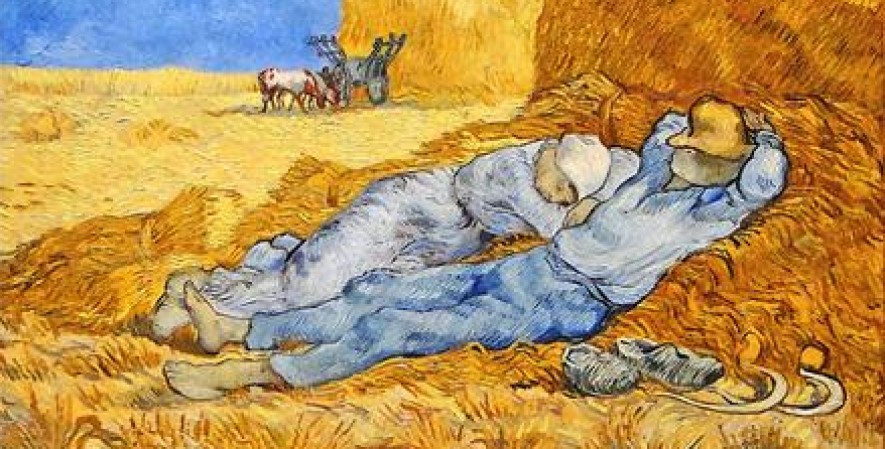

But the story doesn’t end here. Even as Parkway Drive becomes home, a blessing takes hold when I head south to St. John’s. It fills me as I wonder why some horses wear blankets and others don’t. It abides with me as I work in the pastor’s study, try to offer the folks a good word on Sunday morning, and eat chicken pie with the seniors at the Stone Arch Restaurant: The land and its stewards reach out and pull me in, as if to rest against the bosom of the Lord.

Winter is being coy with us in northwestern Pennsylvania, but my view of the blonde corn stubble out my study window calms my heart. And the parishioners I’ve gotten to know wear their goodness without pretense.

The other day Parish Secretary Jodi got a call reporting that we have roof leaks dripping into the church lounge. She hadn’t finished passing along the news when Anne and Dave’s car pulled up in the parking lot. They had also received word and were coming to check things out.

The problem and temporary fix were quickly settled, but in a fifteen-minute crevice of the morning, Dave and I talked. More importantly, I listened. Amazing what you can learn in a quarter of an hour.

Dave is a retired veterinarian who restricted his practice to cows. He still has twenty of them, three of which are calving. You can take the veterinarian out of the cattle, but apparently you can’t take the cattle out of the veterinarian. I mention this detail because Dave had been overseeing developments before showing up at church and had work clothes on: think dusty Carhartt-type coat and a long-punished hat with earflaps aspiring to be wings. Anne tried unsuccessfully to smooth those flaps, but Dave said, “I like it this way.”

Confession #1: I want to be like this guy. If his hat looks poised for flight, so what. It feels right on his head. And, really, isn’t that what counts when you’re making sure cows get off to a good start in life?

Confession #2: It took me a few seconds to open up my ears. How long have I known that wisdom isn’t restricted to the monk’s cell or the desert hermit’s cave or the scholar’s podium? Riches for mind and soul can also germinate under a quirky lid. Fortunately, I forget easily, but remember with light speed.

Confession #3: The instructions I gave myself wouldn’t suit a sermon, so I’ll give the G (all ages admitted) version: “Listen up, pal,” I thought, “this man has something to teach you.” I caught two lessons in five minutes, not a bad return on the time investment.

Lesson #1: Dave said, “Everything is born to die.” I recalled at once some years ago asking farmer and author Joel Salatin about vegetarianism, and his response was similar. Dave brought me back again to the possibility that death’s inevitability is less important than how it’s attended. He described slaughterhouses he had visited where the cows walked a curved chute toward a pitch-black elevator. Cows will hug an outside wall following a curve—natural to them, I guess. And when they emerge from the darkness, their end comes immediately. No fear or trauma, no months of anxiety about diagnoses and treatments and the dying of the light.

Everything is born to die: not a callous statement or lazy rationalization, but a confession. Salatin pointed out to me the arrogant assumption that the death of a pig is necessarily more noteworthy than the cooking of a carrot. Sounds silly until you understand that the observation lies far down the anthropocentric path. Salatin didn’t use that fancy word, but that’s what he meant. Parishioner Dave can speak for himself, but I bet he knows more about life and death than I do. His days involve walking land I only visit and touching animals I know from a distance. Best to learn from him with an open, humble spirit.

Lesson #2: Dave cares about those twenty cows. His words, voice and manner had a tenderness about them. An animal’s suffering or an injury to the land would pain him. He doesn’t emote as I do, but I know love when I see it—not the love shown in a photograph of an infant in a boot, but the love visible in a retired veterinarian keeping vigil to be sure a calf gets on its feet. The calf will grow and be sold someday, but it’s loved no less for that.

I gathered all this from a man wearing a hat with wings and speaking softly. Acreage in counties close to St. John’s wouldn’t suit me, but traveling there a few times a week is healing my spirit in ways I’m only beginning to understand. And I didn’t count on being edified by folks like Dave and Anne, who would read this and probably tell me to quit fussing.

Rooftops and bare trees on Parkway Drive

But I’m going to fuss. Tonight I’ll fall asleep next to beloved Kathy in a blue-collar hermitage. And tomorrow morning I’ll drive an hour to tend my flock in a place where you can see the stars.

Right now, across Parkway Drive, a neighbor puts away fake garland. Kathy just lay down on the couch and mentioned that from her angle, all you can see is rooftops and bare trees.

I thought, “You could almost be in the country.”

I’ve been going to bed by 9:00 p.m. lately and waking up several times during the night–changes in established rhythms. Wife Kathy and I have pruned home to 1000 square feet. My pastor work has slimmed to part-time to make room for writing. And Kathy cries out whenever she rolls over.

I’ve been going to bed by 9:00 p.m. lately and waking up several times during the night–changes in established rhythms. Wife Kathy and I have pruned home to 1000 square feet. My pastor work has slimmed to part-time to make room for writing. And Kathy cries out whenever she rolls over.