Far more than decent, the day verged on merry. Kathy and I safely traversed the afternoon, walked foxhound Sherlock Holmes, and settled in for ABC’s World News Tonight with David Muir. That last step was a mistake. Continue reading

Far more than decent, the day verged on merry. Kathy and I safely traversed the afternoon, walked foxhound Sherlock Holmes, and settled in for ABC’s World News Tonight with David Muir. That last step was a mistake. Continue reading

Yes, Mom, I know it’s possible that I’ve written this letter only for myself—a hopeful, neurotic middle-aged man—and that you may be nothing more than the bone and cinder your children buried in June of 1998. But I can’t help hoping that existence is as abiding as your Christmas cactus and as fair as your great-grandson Cole. Continue reading

This gallery contains 2 photos.

Oniontown Pastoral The Orphan’s Question: Where Is Love? Kathy’s breaths of sleep come and go. Awake at dawn, I’m in a high school choir concert 45 years ago, a musical’s lyrics forming behind my closed lips: Where is love? Does … Continue reading

Oniontown Pastoral: When Kathy Walks Away Love’s not Time’s fool, though rosy lips and cheeks Within his bending sickle’s compass come. (William Shakespeare, Sonnet 116) Out of an abundance of caution, that was the reason, I suppose. The Colemans of … Continue reading

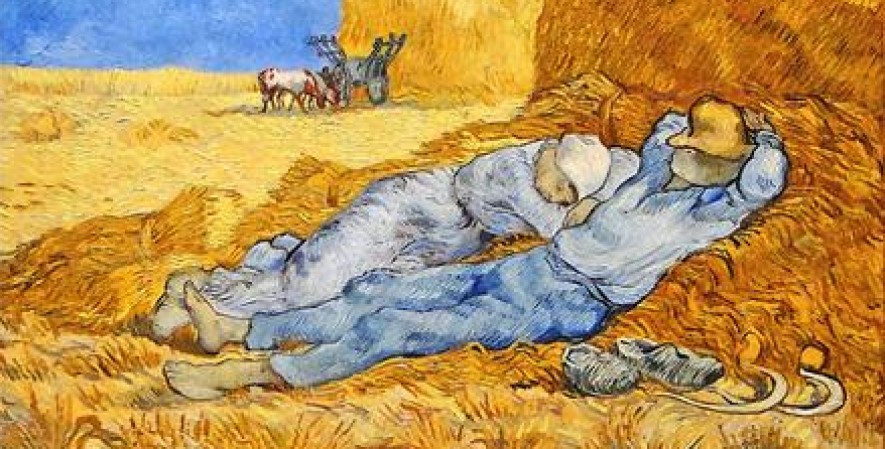

Oniontown Pastoral: Afternoon of the Gladdened Heart

If my blessing had a face, it would belong to a three-year-old as yet unpunished by disappointment. Time ages us all, but it’s toil that paints pale bruises under our eyes and sculpts wrinkles and jowls. Anyway, the darling cheeks of my blessing would be smeared with grass and mud. A mother would lick her thumb and go after the mess, but the child would twist loose before the job was done.

This is for the best. What catches my aging breath isn’t in the child’s face alone, but in the anointing of sweat, dirt and spit. And especially in what once annoyed me, but now returns as longing: Being pulled close by my mother, looked at with what only ancient Greek fully captures, agape, and gently tended.

The blessing was simple: Kathy and John Coleman’s grandsons, six and four, played in our muddy backyard. They filled milk jugs from the hose and made a pond behind our garage. Given enough time, they would have built a moat. As Cole and Killian troweled new layers of crud on their skin and jeans, son-in-law Matt and son Micah sunk posts in for a fence, and pregnant daughter Elena and Kathy kept an eye on the boys and talked. I sat on the steps, mindful of the sun. The shepherd’s pie I had labored over bubbled in the oven.

My efforts, I confess, were fortified by a splash of Cabernet Sauvignon. Having skipped lunch, I wasn’t drunk, but my heart was gladdened. In this condition, I watched with outsized pleasure Cole and Killian, whom Kathy and I hadn’t seen much during the Coronavirus pandemic, lose themselves in the possibilities and wonder of their grandparents’ yard. For good or ill, we adults had decided to loosen the restrictions within our family.

Many grandparents live far away from their grandchildren, an arrangement that would dig a ditch down the middle of our lives. As the weeks wore on, we saw the boys from six feet away. We didn’t hold their hands or kiss them on top of the head or pick them up. Kathy got weepy when the subject of being separated from Cole and Killian came up and crossed her arms in a hug that came up empty.

If having grandchildren were worship, then those boys perching on my lap and leaning into my chest would be Holy Communion. I never take for granted being Pop next to my wife’s Grandma Daffy and the good fortune of our adult children choosing to reside nearby.

So the blessing was mostly this: Peace in the family, laughter in the yard, grandsons who come near again. Every once in a while a gathering of minutes is so right as to seem otherworldly. Friend Jodi told me about a day long ago when she and her brother were fishing on calm water. Leaning back in his seat and looking at the sky, he said, “I feel sorry for anybody that’s not us right now.”

That’s one way of putting it—grace tells the seconds to hush and mercy is perfect air passing over your arms and face.

Man, was I happy. Who knows why, then, my late father joined me on the steps? He would have rolled his eyes at my glass of red restorative. He was a Schlitz man, not an alcoholic, but in leisure hours he could dent a case.

50 years ago I sat with Dad on Grandma and Grandpa Miller’s porch steps. No talk. The beers had gone down quickly, and Mom was mad that he had gotten a fat tongue before family dinner. He stared somewhere far off, beyond Horton Avenue. Dad was in the dog house for good reason, but I’ll never forget how licked he was. My parents weren’t made for each other, that’s all. Sad time stretched out in front of him–and Mom, too, I know–long loveless summers of little but getting by.

It was strange, but lovely, to recall my father’s saddened heart while the great-grandsons he never met ran carefree “in the sun that is young once only.” My unmerited joy rested Dad’s defeat on its shoulder and was the sweeter for it. Maybe this is why I thought of him. That could easily have been me decades ago, slack jawed and dazed on the in-laws’ steps, a son keeping vigil. Lucky is what I am.

The face of gladness is young, fresh with promise, but it’s not real without the streaks of earth and blades of grass. That’s how I know it belongs to me.

Oniontown Pastoral: What Will Happen with Ray?

My phone will ring. It will ring now in the middle of a sentence or during my siesta or when wife Kathy is telling me about her day. The name Ray will roll across my screen, and my chest will tighten with annoyance. I’m ashamed to say so. The deal is, if I’m occupied—and what I’ve just mentioned counts—then I don’t answer. Otherwise, I pick up.

Used to be Ray would ask for a ride to get tobacco or to borrow money. He always paid me back, but the loans messed with my cashflow. Other than an occasional fiver, the Pastor John Bank is closed.

I still take him here and there. He gives me a few bucks for gas and thanks me over and over. Occasionally he can’t help himself and calls me an hour after I drop him back off at home: “Pastor, I just wanted tell you how much I appreciate everything you do for me.”

Ray’s mental illness is chronic. If there’s a psychiatric condition, it has paid him a visit. I don’t know all his medications, but the man sags, drags and droops—same with his jeans, suspenders not withstanding. But he still gets sick. That’s what he calls his collective turmoil, whether it’s fretting about somebody breaking in and stealing his debit card or being scared that God is punishing him for smoking or some other trifle.

“Hey, Raymond, how the heck are you?” is my usual salutation.

“I’m really sick today, Pastor,” he’ll say first thing. “Please pray for me.” We talk for a minute, maybe two.

Sometimes he responds, “You know, I’m doing pretty good today, buddy,” and I get another feeling in my chest, a lightness. We chat, enjoying the nonchalant fact that he’s OK.

And so Ray goes. Tolerable days string together, then the old anvil falls. He checks himself into the hospital, where a doctor tweaks his meds. After a week he gets released, does OK for a while, then, here we go again.

Ray doesn’t have many interests to leaven his lonely hours folded up in a broken recliner. He once collected beer steins, record albums and even cigar humidors, but every diversion has a way of turning into an obsession that crushes all good sense.

To his credit, Ray has gotten better at holding binge behavior at bay, except with Starlight peppermints that constantly clack against his dentures. When the smoking habit reigns, his fingertips go rusty blonde.

To his credit, Ray has gotten better at holding binge behavior at bay, except with Starlight peppermints that constantly clack against his dentures. When the smoking habit reigns, his fingertips go rusty blonde.

As long as he’s feeling alright, my buddy is content. He reads chapters of the Bible over the phone with friends and is satisfied with a diet of plain boloney sandwiches and Cornflakes.

At 62, though, Ray is never free of legitimate worry about his future.

“I don’t know what’s going to happen with me,” he said the other day from my passenger seat. “I’ll probably end up in Warren.”

Warren State Hospital, that is. When I was a kid in northwest Pennsylvania, “North Warren” meant “loony bin.” Sad, but that’s how it was.

But what I heard Ray saying was, “I expect to be forsaken.”

And I heard, “I’m going to completely lose my mind, and nobody will care one way or the other.”

A couple years ago, Ray almost made me lose my mind. His illness was particularly severe, and he would call me eight to ten times a day. When I brought the number to his attention, he had no idea.

“I’m sorry, Pastor,” he apologized. “I’m not playing with a full deck.”

“I know, Ray. I understand,” I assured him, swallowing frustration.

He is infinitely better now. So why is it that when Ray runs across my screen these days, I react inside like he had whacked my thumb with a hammer? Not every time, but often enough.

Other than a ride or a cup of Starbucks coffee, all Ray wants is a moment. He wants a friend to give him hope that once he runs out of cards entirely, his name will still mean something to somebody.

When Ray said, “I don’t know what’s going to happen with me,” it was as if God leaned in close and asked, “So, what will it be, John? Will my son be forsaken?”

If you ask me what faith is, I say it’s believing that when Ray falls asleep every night, God is nowhere more present than in his room. It’s dreaming that God looks at my friend’s face in the dark and sighs.

Faith is answering my phone.

Oniontown Pastoral: The Human Moment

I was peeved. Pittsburgh Avenue in Erie was bustling on Saturday afternoon, and Mr. Pokey Joe had no business jaywalking while cars, including mine, bore down on him.

Then I recognized his predicament. He had a bum leg and, like me, was past his prime. Each step made him wince. The trek to a legal crosswalk would have been an ordeal, especially with a jammed knapsack thudding against his back.

My peevishness slunk away, tail between its legs. Of course, I was relieved not to have run the fellow over, but grateful as well for a human moment. That is, a connection with another person’s reality, a chance to remember in the midst of a day’s jostle and distraction that the faces I encounter belong to pilgrims worthy of my consideration.

My life is mostly a pilgrimage from one human moment to the next. This past week, for example, I found myself at McCartney Feed and Hardware in Fredonia. I paid for 25 pounds of deluxe birdseed—call me extravagant—and took my receipt across the way to a huge barn.

As I waited, a machine reaching from floor to ceiling growled, rattled and rumbled. What was this behemoth all about? Thankfully, it hushed up as a young man arrived with my purchase.

I said thanks and turned to leave, but felt like I was ending a sentence with a preposition out of mere laziness.

“Hey, what does that thing do?” I asked.

“Oh, that’s a grinder,” he said.

Another member of the McCartney crew arrived and told me they would be putting oats in soon, but first they had to get residue out of the machine.

“Ah,” I said, “so you have to let the grinder clear its throat?”

They both nodded and laughed. I thanked them and drove off. That was about it.

I can’t swear to the specifics of what those McCartney’s guys explained to me, but here’s what I know. Carrying birdseed through the sunshine from barn to car, I was glad. All was well with my soul. The world seemed right, except for the odor of fresh manure, which my city nostrils haven’t yet learned to savor.

I had showed up with dollars, but the transaction was about people being together in harmony, however briefly.

“Oh, there you go again, John,” you’re thinking, “always with your head up in the clouds.”

Hardly! This is probably a good time to mention a caveat. If you want to collect human moments, prepare to be served joy and dismay in equal helpings.

Syrian boy Omran Daqneesh comes to mind. Pulled stunned and bloody from building rubble and set alone in an ambulance, he stares at me still, three years after a bombing raid ravaged his neighborhood. Maybe you saw his face on television.

Sad to say, for a sympathetic conscience, human moments arrive without permission. Go ahead, close your eyes. It won’t matter. Like light, love comprehendeth the darkness.

My wife Kathy is an oncology nurse, and she brings home impressions of folks passing through cancer’s lonesome shadows. Never names, ever, but plenty of heartache, including her own.

Sipping pinot noir as the evening news recounts inhumane moments, I embrace souls in Kathy’s care whose ends are near. One of them weighs next to nothing. Eternity is barreling toward her. She said through tears, “I don’t feel good.” The understatement catches in my throat.

I can see her. She wears a sleeveless summer dress like the ones my Aunt Mart loved, flowery prints. The poor lady’s hands, all scarlet bruises and torn skin, tremble in mine. She is weary, afraid, not ready to die.

Oh, yes, I can hear you thinking to yourself again. “John, stop dwelling on other people’s problems!”

No, I won’t. The fact is, you can’t have human moments all one way or all the other. If I didn’t appreciate a nameless patient’s suffering, then I wouldn’t have spotted bliss at a recent wedding. The couple made promises, and I pronounced them husband and wife. Minutes later the bride leaned into the groom, her smile as close to heaven as I expect to witness this side of glory.

So I receive Omran and the bride as both package deal and personal obligation. The foreign boy and domestic woman and the McCartney guys and wincing stranger abide under my watch.

So I receive Omran and the bride as both package deal and personal obligation. The foreign boy and domestic woman and the McCartney guys and wincing stranger abide under my watch.

That’s how human moments work. When I neglect any neighbor near or far, I turn my back on the Creator who made this Oniontown pastor a human being in the first place.

Love Begets Love

Dogs have occupied my thoughts lately, mostly because foxhound Sherlock Holmes, who moved in last December, finally reached a milestone that his predecessor Watson had licked from day one. Our lanky detective hopped up on our queen-sized bed, curled into a big boney oval at my feet and slept there all night long. His first night with us, black lab-terrier mix Watson yipped and yiped in his crate until Kathy and I relented and nestled him between us.

This was adorable, but risky. He wasn’t housebroken. Whether by miracle or fate, Watson leaked not a drop. I suppose he knew that he had found room in the safest of inns. There wasn’t more than a handful of nights from 2004 to 2016 that Watson didn’t snore in the crook of Kathy’s leg or under the shelter my arm, his head pressing my nose flat.

His stay with us was sickeningly affectionate from the start. Sherlock Holmes, on the other hand, has been sizing us up at his own cautious pace. I don’t blame him. He endured trauma of some sort during his three years before landing at the shelter where we found him.

The nerved up guy becomes a maelstrom of fang and claw whenever we try to administer medicine. No malice is intended. He’ll let me dig deep into his ears for some heavenly itching—my fingertips nearly meet at the center of his skull—but let me sneak a dab of ointment into the transaction, and he beats a retreat and says, “Et tu, Brute!”

Our veterinarian prescribed a sedative should we need to bring our leggy pal in for treatment. Sherlock’s initial checkup was bananas. Imagine subduing a creature wildly swinging four fur-covered shillelaghs tipped with little spikes. Again, it’s nothing personal, only no injections or palpating permitted.

So the intimacy between dog and human that profoundly nourishes both has been slow to take hold. Son Micah smears peanut butter on his nose to invite a kiss. Meanwhile, Kathy and I have patted our mattress and pleaded ourselves hoarse: “Come on, buddy. Come up with us.”

As so often happens in my life, the milestone passed quietly and unbidden. The other day Sherlock was suddenly up on the bed, sleeping as if engaged in a routine. Same thing happened the following night, but since then he has occupied the couch.

We’re not complaining, though. When his doggy synapses so compel him, he’ll arrive to hog our legroom and give both of us a reassuring pat on the spirit. Meanwhile, the Colemans have decided to let Watson of blessed memory be Watson and let Holmes, here among the quick, be Holmes.

Not that there’s any alternative. What’s true of dogs is true of humans and anybody else with hearts and eyeballs. During a recent session of chin wagging, friend Judi put the matter perfectly. As we lamented folks with disputatious personalities, she tapped a verbal gavel: “Sometimes you have to accept people the way they are.”

The late Fred Rogers would agree, and so do I. Obviously the path of acceptance shouldn’t lead to staying in an abusive relationship, hobnobbing with a psychopath or spooning with a king cobra, whose venom the Encyclopaedia Britannica claims can “kill an elephant in just a few hours.”

Old pal Watson’s worst offense was sudden crystal-shattering barks for no discernible reason. We learned to live with it. Sherlock’s baying is equally loud, but we know exactly what he’s fussing about.

When I get home in an hour, he’ll be jonesing to run. I mean, he sprints with such abandon that his back legs can’t keep up with his front. The result: those back legs dangle behind his body, momentarily swaying carefree until they touch down again.

Until I drive Sherlock to the dog park’s glorious acres, he’ll hoop and whine and wander about the house, clicking his nails on the hardwood floor. There’s no changing this foxhound’s stripes or taming what his Creator intended for him.

Funny thing is, I’ve come to love our goofy dog exactly as he is. With each passing day, his place in the family grows more sweet and easy. And this is the moral, if you ask me. Acceptance begets acceptance. Love begets love.

I can see this truth in Sherlock’s face—I swear. We let him be who he is, and he understands somehow or other, “These people love me. I think I’m going to like it here.”

The Trouble with Love

“Our job is to love others without stopping to inquire whether or not they are worthy.” (Thomas Merton in Disputed Questions).

Most often breathtaking is used figuratively, but in recent days I’ve said to myself, “John, you’re not breathing. Stop and breathe.” Mass murders, hatred, relentless falsehoods and absurdities arrive in torrents.

Saturday, October 27th: Tree of Life Synagogue in Pittsburgh, eleven dead. Tuesday, November 6th: The scorched earth of midterm elections. Wednesday, November 7th: Thirteen dead—most of them younger than my own children—in Thousand Oaks, California. To these news items add that state’s wildfires, which according to latest reports are 35% contained.

But let’s set aside Mother Nature for the moment. Disasters of human agency take everyone’s breath away, and many Americans are further deflated by the likelihood that governmental leaders won’t lift a finger to prevent further loss of life.

Political motivations are legion, the bottom-line being that innocents’ safety ranks far below constituents’ hobbies and proclivities. Transparent lies, lame as a crumb-dusted child denying raiding the cookie jar, are piled so high that responsible citizens grow disoriented and exhausted.

Any spare energy may well be absorbed by hatred, which is eager to throw off its gloves and start swinging. Present circumstances are practically designed to bring out the fighters in everybody. Some of us struggle to hold rage against the ropes while others gleefully talk trash and punch below the belt.

Sad to say, you can sometimes find me in the ring, too. In my mind I heap insults and ridicule on my fellow citizens’ heads before remembering Thomas Merton’s instruction: “Our job is to love others without stopping to inquire whether or not they are worthy.”

As I pause over these words, anger rises in my chest. The exhortation to love is Pollyannaish. The task is difficult. Who can accept it? There’s a physiological response when you look at folks you really want to punch in the face and remember you’re supposed to love them.

My mother, God rest her, took her upset out on doors. As a teenager I once made her so mad that she slammed the basement door, took two steps away, then returned for seconds.

Even in the closest of relationships, love is trying. It can be like digging a pointless ditch with a swizzle stick when all you want to do is put said ditch to good purpose by shoving the person you can’t stand into it and shoveling in wet dirt?

Yet we know that this isn’t the Christian way. Actually, millions across the belief spectrum would say that they are called by conscience to love of neighbor and rejection of hatred. The problem is, anyone who has walked the path of understanding and compassion for long knows that confusion dominates comfort, deprivation overwhelms fulfillment. Being steadfast takes stamina.

This is why my gait appears drunken. Every fork tempts me toward a destination that rolls out the red carpet for my worst impulses: “Nobody deserves your consideration. They’re not really your neighbors. Put yourself first, others can pound salt. Let your tongue be barbed wire.”

All that keeps me from staggering hopelessly far in the wrong direction is one crucial insight and a whisper of grace. Love is a roomy term. Contrary to popular thought, “love” and “affectionate regard” aren’t attached at the hip. The latter simply can’t be commanded, which is convenient, since the love humanity now starves for has nothing to do with cuddling or playing footsie.

In Conjectures of a Guilty Bystander, Merton has a revelation about his earthly brothers and sisters while visiting Louisville, Kentucky: “At the corner of Fourth and Walnut, in the center of the shopping district, I was suddenly overwhelmed with the realization that I loved all these people, that they were mine and I theirs, that we could not be alien to one another even though we were total strangers.”

Merton recognized in the city’s shoppers “the secret beauty of their hearts.” He knew that they were children of the same Creator, beloved of the same God, and wanted to tell them that they were “all walking around shining like the sun.” They could also be monumental pains in the neck or far worse.

I occasionally want to give Thomas Merton’s hermitage door a few slams, but a quiet grace visits, filling me with belief: God calls me to love without reservation, especially when the effort seems foolish, even embarrassing—a little like supposing that some good might come from a man hanging on a cross.

I Won’t Be Ashamed of Love

The 1993 movie Philadelphia teaches the powerful lesson that love is something to be proud of, even though folks may find certain expressions of it hard to honor at first. On the soundtrack, a Neil Young song, also named after the City of Brotherly Love, resonates with me, especially the line “I won’t be ashamed of love.” The protagonist is a gay lawyer dying of AIDS. My sister Cathy is married to Betsy Ann, and sister Cindy is married to Linda. Far from feeling shame, these kind and upright women ought to be proud.

But as moving as Neil Young’s words are in context, their message begs to be taken down from the screen and worn like a wedding ring. Love isn’t something you put on when it feels good and take off when it proves inconvenient.

Here in 2018 the temptation to compartmentalize love and all the rest of our emotions is great. Our tear ducts, for example, work overtime for YouTube videos of Christmas puppies and soldiers returning home to surprise loved ones, but an emotional voice in a political debate is often persona non grata. Two Facebook comments show what I’m getting at:

Awww did the bad man hurt ur feewings again

and

You need a safe pwace with a blanky

These responses landed in a sparring match over recent news developments, with one side expressing genuine concern and the other sticking with locker room towel snapping.

I don’t mention specifics here because I’m not looking for a fight. My point is directed to the whole sociopolitical spectrum. Not only won’t I be ashamed of love, I want to be its champion. Americans from many quarters insist that something essential to their identity is under attack, which may explain why we’re always putting up our dukes.

While my own rhetorical fists aren’t raised, my arms are crossed. I admit it, I need a safe pwace with a blanky. Some folks take pleasure in calling people like me a “snowflake.” Nothing new here. Those who drag kindness and compassion into the debate hall used be “pinkos” and “bleeding hearts.” Today, a merely descriptive term, “liberal,” is being wielded as a slur.

Such language is weaponry in what I believe is a war on love. Emotions, the reasoning goes, have no place in policy formation, and those who suggest otherwise deserve a good mansplaining.

I disagree, so with a blanky on my lap, I’ll speak only for myself. Tease the worried and teary-eyed if you like, but you’ll not shame this old softy for a few love-inspired convictions:

As you can imagine, my commitment to love reaches beyond the controversial issues of a given season. Love means putting my iPhone away when somebody is talking to me. It means thanking police officers and soldiers for their service. It means remembering that nothing makes me better than the guy at Erie’s State Street Starbucks who has loud arguments with himself. Nothing. I’m one chromosomal kink, chemical hiccup or bad decision from being in his shoes.

Come to think of it, he hasn’t been around in quite a while. I hope he is OK. He might not understand my concern for him, but I’m sure you can. I’m not ashamed to say that he is worthy of my love.