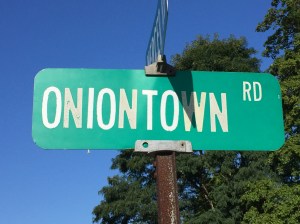

Oniontown Pastoral: Old Floyd and New Floyd

In Memory of Warren Redfoot

Three of us sat around the hospital bed in Warren’s living room: his wife Nancy, daughter Barb, and me. Under the covers was Warren, all 90 pounds of him. Sticking out were his head, shoulders and left arm, which rose and fell throughout our conversation, as if carried on a breeze.

Miracles were coming out of the man’s mouth. Not that all his words made sense, but never mind sense. Warren was speaking in poetry, which takes inscrutable turns and isn’t obliged to be linear.

“I wish I could make myself understood,” he said somewhere in the midst of the quirky grace he was bestowing on us. We assured him that he was doing fine.

What got Warren rolling was this. Barb said, “Dad, do you want to tell Pastor John about Old Floyd and New Floyd?”

He was game. The story, which had been birthed in his imagination the night before, evades transcription, but the gist is simple. The Floyds are either tractors or men, depending on Warren’s memory at the moment. Old Floyd is doing farm work, but eventually breaks down. Then New Floyd shows up and takes over.

As in the mysterious possibilities of dreams, however, the Old Floyd is, in fact, the New Floyd. “Not the same body,” Warren explained, “but the same.”

He was talking—for the love of God!—about resurrection.

Closing his parable with a flourish, Warren pushed aside imaginary clouds and said, “Then the sun came out.”

Then the sun came out.

“Boy,” I managed through a tight throat, “you could add another chapter to that story if you wanted.”

“Another chapter?” he replied, almost incredulous. “Another paragraph. Another sentence!”

I caught his meaning. This fragile man was schooling his pastor about life, death and everlasting hope. Sooner or later, life boils down to finding a good word, taking a single breath, or touching the cheek of your beloved, as Warren did to Nancy. All that this husband knew of tenderness shone forth as he reached for his wife, to ease her sorrow.

Old Floyd—Warren’s father’s name, incidentally—can see New Floyd coming. Time grows short. One more sentence means everything. One more hour. Another kiss.

These thoughts swept me away. My left hand held Warren’s while the right clamped over my mouth. Barb touched my shoulder. For the first time I was nearly undone at a bedside and thought I might have to excuse myself.

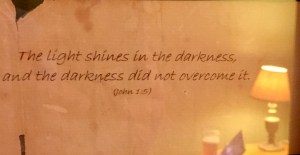

Can you understand? If God leads us to each other to give or receive what we need most, then God, indeed, sent me to Warren and Nancy’s house to receive the assurance of things hoped for, the conviction of things not seen.

Once I regained myself, we shared Holy Communion. Warren’s eyes locked on mine as I held up the bread and cup. No bashful glancing away for either of us, not with eternity so near.

Afterwards Warren asked for a decent swallow of wine to supplement the sliver of bread I had dipped in the chalice and rested on his tongue.

Even though his throat was constricted, I poured him a tiny portion. Never have I seen a believer drink more eagerly. He held the thimble-sized glass above his mouth, the last drop falling on his tongue.

Then Warren said, “I have an urge.”

“An urge?” Barb asked. “An urge for what, Dad?”

“For another Communion,” he said. “Not this one. Another Communion. The next one.”

And then he went on and on about how delicious that wine was. I couldn’t argue.

When Warren seemed to be flagging, I said my goodbyes, but as I reached the door, he called my name. Not “Pastor John” or “Pastor,” only “John,” the name I pray one day to hear God whisper into my ear.

I turned around to face Warren reaching skyward, like Atlas holding up the planet.

I did the same. We kept the silence together.

“Peace?” I finally asked.

He nodded, mighty under the weight of the world: “Peace.”

Driving home, I sighed to hold off tears. “The Spirit helps us in our weakness,” I remembered, “for we do not know how to pray as we ought, but that very Spirit intercedes for us with sighs too deep for words.”

Old and new.

Warren was every bit the Spirit to me. Maybe for a moment, like those Floyds, they were the same. I don’t know. But what I can say for sure is this: When my skinny old friend gave me a foretaste of the feast to come, the beauty almost made me go to pieces.