I consider it an outrage that I woke yesterday morning with the well-intended but terrible song “To All the Girls I’ve Loved Before” playing in my head. Who sang that? Was it Placido Domingo and John Denver? No. That was another sweet one, “Perhaps Love,” or as Placido sang it, “Puh-da-hahps Love.” Was it Willie Nelson and Domingo? Close. Willie Nelson and Julio Iglesias!

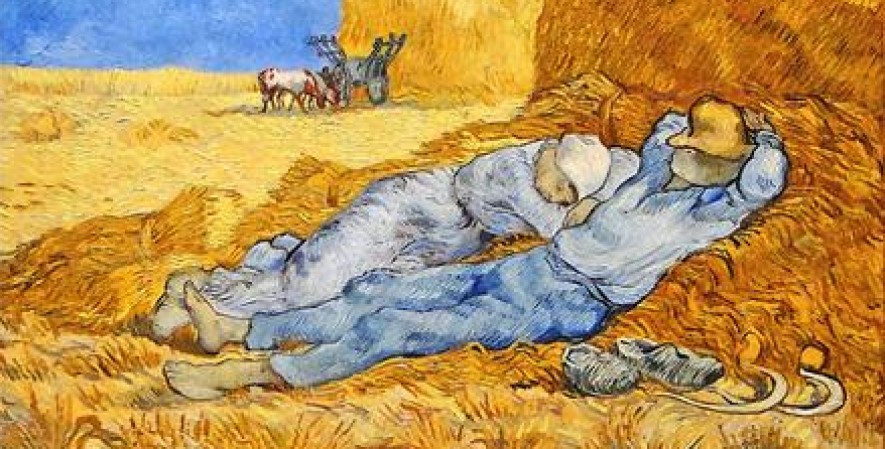

I wish the tune would go away, but I’m grateful for the thought it coaxed out of me. In their hit, Willie and Julio take on the character of itinerant Don Juans, loving a girl at every stop on tour—oh, brother! Wherever they go, they love. I, on the other hand, am an itinerant contemplative, praying and napping (my two requirements for contemplation, anyway) wherever I go. All I need is a decent spot to sit or recline.

Years ago most midday rest came at home, but now the pastor’s study regularly hosts blessed oblivion, as does the car if I’m faced with a long wait. And, of course, travel has never prevented napping. I’ve taken siestas in cars and on buses, trains, and ships, but never on a plane–too nervous. I’ve probably napped in over half of the fifty states. In the next few years I hope to nap in Europe.

And prayer: I’m apt to pray wherever I can sit down.

A couple of places you’d think would be good for contemplation actually don’t work very well.

I don’t often need to nap in public, but I’m always praying out in the open. Some people get mad about their doctor being behind schedule, but unless I’ve got somewhere else to be, I close my eyes, sit still, and breathe. I’ve prayed in a probation office waiting room a few times and even managed it in the natter of the 30th Street Station in Philadelphia. In a coffee shop? Yes. In a department store while wife Kathy tries on clothes? Sure. In a library? Absolutely. I used to feel self-conscious when folks passed by, but what for? I don’t mind being known as the pudgy guy with owl glasses who sits around with his eyes closed.

When this long, cold spring on the shore of Lake Erie breaks, I’ll take the show outside, too: the front porch, back patio, and Presque Isle State Park are all in the running. In fact, if I had more time today, I’d find some shade at Presque Isle and chase down an hour’s siesta with half-an-hour’s prayer. It’s sunny and 77 degrees. The rest of this week won’t be so nice, but before long I’ll have more places to nap and pray than I know what to do with. For now I’ll settle for an hour in my own bed–that is, if I can shut out these playboys singing “to all the girls [they] once caressed.” “And may [they] say [they’ve] held the best.” Ugh!